From the Desk of John L. Harrington

Chairman of the Board & Trustees, Yawkey Foundation

October 2023

Dear Friends,

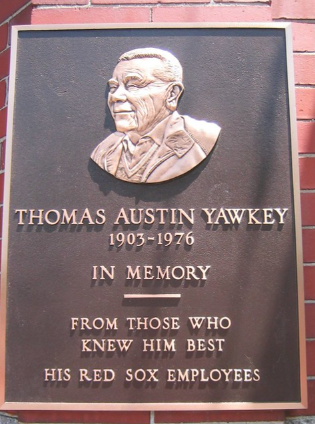

I write this letter on the occasion of a meaningful milestone anniversary year in Boston baseball history: 2023 marks the 90th anniversary of Tom Yawkey’s purchase of the Red Sox. A failing franchise at the time of the sale, Yawkey renovated and saved Fenway Park, rebuilt the team, and saw it reach three World Series – and fall heartbreakingly short in the seventh game each time.

There was never any question about Yawkey’s dedication to the club or to the city of Boston. He spent millions on the team, and spared no expense to demonstrate how he valued each player – professionally and personally. Among the many instances of confidential support he discreetly made to players and their families experiencing financial or medical hardships, these gestures were offered to more players than one would imagine.

Yawkey’s role in the fight against childhood cancer provided the resources and exposure needed to catapult Dr. Sidney Farber and the “Jimmy Fund” into an iconic presence in New England by designating it the “Official Charity of the Boston Red Sox” in 1953. It would be an understatement to say that the commitment of both the team and Yawkey’s personal resources changed the lives of generations of individuals and families dealing with a cancer diagnosis.

It is well known that Tom Yawkey and his wife, Jean Yawkey, made sure that when the team was sold to new ownership in 2002, after more than 70 years of Yawkey-family ownership, the proceeds for the entire Yawkey interest as majority shareholder – more than $400 million—would go directly to the Yawkey Foundation to continue their legacy of charitable giving. Indeed, in 2010, when 40 of America’s wealthiest people committed to giving the majority of their wealth to address some of society’s most pressing problems through the “Giving Pledge,” it struck a familiar chord – because more than 50 years ago, Tom had made arrangements to achieve that same goal by designing his own personal Yawkey way of continuing this legacy of giving in perpetuity through the Yawkey Foundation.

These are just a few examples of how this Detroit-born, New York-raised man demonstrated his deep dedication to his adopted home of Boston – discreetly, thoughtfully, and without fanfare. Yet, there remain serious misrepresentations of his actions, character, and values – notably by those without firsthand relationships or interactions with Tom – that inaccurately portray how he lived his life; how he treated others from different backgrounds, races, and ethnicities; and how he approached the business of building a world-class baseball team and the country’s beloved, iconic Fenway Park. Those who knew Tom, those individuals who were fortunate enough to directly work and spend time with him during his lifetime, have attested to his nature as a private, reserved, and kind man.

False narratives that are neither true nor fair continue to perpetuate in certain circles – specifically, charges that he was in the stands when the team held a tryout for Jackie Robinson in 1945. This false allegation was debunked by journalists of the day. I know first-hand, and our Trustees believe, that Tom demonstrated his respect and admiration for baseball players and all people, regardless of the color of their skin, and in a manner that reflected his character – loyal, understated, and without ulterior motives of recognition or reputational positioning. And to that point, a much-overlooked fact is that the story of integrating baseball in Boston began in 1933, well before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier when Tom Yawkey’s Red Sox signed Latino Mel Almada, the first Mexican-born player in Boston Red Sox and Major League Baseball history. Almada played four years with the Red Sox and was inducted into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973. So when we read or hear falsehoods that contradict what we know are the true facts, we are left with feelings of sadness and betrayal. Now is the time to put an end to this hurtful, inaccurate myth.

In addition to being a true baseball fan, Tom’s Yale education positioned him as a savvy businessman, and he pursued an intentional strategy to build what he hoped would be a world-class baseball team. He was known for his commitment to recruiting experienced, top-talent players who were at the top of their game, regardless of race. Simultaneously, he invested in building a farm system that would develop less-experienced players to grow a talent pipeline into the Major League roster – again, regardless of race. This two-pronged approach is well documented through a timeline supported by contemporaneous media coverage that clearly shows that well before 1959, the Red Sox were working hard to bring Major League-quality Black ballplayers to the club through both proven and high-potential player talent pools.

The Red Sox signed their first Black Player, Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, to a minor league contract in 1950. In 1952, the team made serious bids for two other Black players—Double-A pitcher Bill Greason and Black center fielder Larry Doby. (At the time, offers were only made to teams, not players.) The St. Louis Cardinals declined to part with Greason, despite an offer three times the average baseball salary at the time, and the Cleveland Indians refused repeated Red Sox offers for Doby.

In 1953 the Red Sox signed Black pitcher Earl Wilson to a minor league contract, and in 1954 approached the Dodgers about acquiring Black second baseman and future All-Star Charlie Neal with an offer comparable to Ted Williams’ salary, then the highest-paid baseball player. The Dodgers said no. That same year, the Sox bid for Black outfielder Al Smith from the Indians but were rebuffed again.

Then, after four years of experience in the Sox minor leagues and after a 1957 Spring Training game in which Wilson beat the team’s major league squad, the Red Sox determined that Wilson was ready to be promoted to the majors. The plan was set: Wilson would be called up to play in the 1957 season, thereby integrating the team’s Major League roster. Except before he could pitch an inning in Fenway Park, Wilson received his draft notice. He enlisted in the Marines and served two years. While Wilson was away, the Red Sox finally integrated their Major League roster with the promotion of Elijah “Pumpsie” Green in 1959. Wilson followed him a few weeks later after completing his military obligation and pitched for the next seven seasons. We respectfully urge readers to understand the true story of TomYawkey, and the baseball team’s sincere and credible efforts to integrate the team prior to 1959, to visit the Integration Timeline, which is accessible through links and QR code at the end of this document.

As the Trustees and I are entrusted with the privilege of stewarding Tom’s legacy, we foster relationships that we know would have resonated with Tom if he were still here with us today. Poignantly, this includes a partnership with the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, NY – a place that was very special to Tom and Jean throughout their lifetimes.

In June 2023, The Hall announced the Black Baseball Initiative, supported in part by the Yawkey Foundation and anchored by a new permanent exhibit titled “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball.” This initiative reveals the deep connections between baseball and Black America and shares inspiring stories of those who overcame seemingly insurmountable challenges to play the game they loved. We consider it appropriate, fitting, and a profound honor that the new exhibit will be on view in the Yawkey Gallery of the National Baseball Hall of Fame when it opens in spring 2024.

While these efforts and facts do not wash away the deeply regrettable actuality of the Red Sox being the last team to integrate, they nevertheless present a more complex and complete picture of Yawkey’s efforts to sign Black players. The irrefutable, well-documented facts confirming the team’s sincere commitment – and proven actions – to find and promote Black ballplayers to the Major League club are indisputable. It is with deep regret that we witness how these facts have been largely overlooked or, worse, ignored.

As stewards of the Yawkey’s philanthropic commitment, which is inextricably grounded in the couple’s lived values and actions throughout their lifetimes, we have only one course of action: to continue the legacy of kindness, generosity, and grace that was demonstrated by Tom and Jean during their lifetimes.

Just as Tom recognized and celebrated baseball excellence and players regardless of background and race, the Foundation in their name will continue to perpetuate the good of the game, as we do today through our longstanding, cherished relationship with the Jackie Robinson Foundation & Jackie Robinson Museum, a partnership based on the friendship forged more than 40 years ago between Jean Yawkey and Jackie’s wife, Rachel Robinson.

Furthermore, just as Tom recognized the challenges of individuals and families without the resources to achieve their potential and ability to thrive, the Foundation will carry on this commitment to providing support to people and communities in need.

And perpetuating Tom’s intersecting passions for wildlife conservation, South Carolina’s Low Country, and the proud history of the Low Country people, the Foundation will continue to invest in partnerships that reflect his love for the region.

In closing, the Trustees and I acknowledge the obvious reality that history is not static. Facts and anecdotes are often revised when old information rises to the surface and is viewed through a current lens, especially in the digital age. Yet it is the same phenomenon of digitalization of media archives –specifically from the 1940s, 1950s, and beyond – that has enabled us to validate stories shared by those who knew Tom, attesting that his compassion and quiet generosity were extended to people of all backgrounds, races, and ethnicities.

As we contemplate the stories behind recent Yawkey Foundation partnerships, such as the New England Sports Museum’s “Summer of Love: 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox” exhibit and the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s exhibit, “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball,” we are reminded about what his leadership made possible for players, fans and the broader Boston community.

And we are grateful that in Tom Yawkey’s case, the facts available to see him in a new, fuller, and fair light are more readily available to those seeking to understand the true measure of the man – indeed, facts which have been there all along.

Chairman